The following is a transcript of the talk I delivered at TEDxGlasgow earlier this month. If you'd rather watch than read, the video is above.

In January this year, Google announced that YouTube had passed a significant milestone; 60 hours of video are now uploaded to the platform every single minute. That’s one hour of new content for every second that passes in the real world.

That’s truly incredible. If you wanted to catch up with everything uploaded over a ten minute period, you’d have to watch YouTube 24 hours a day for 25 days.

In that same minute, 140,000 photos are uploaded to Facebook – 200 million a day. Couple that with the fact there are now more than two and a half billion camera phones in use around the world, and you realise our ability to collectively create and store visually rich content has become immense. And it’s only widening.

I’d argue the majority of this content arrives on the internet to be shared in the here and now – we don’t expect it to last. But by sharing it in the present moment we’re creating, almost unwittingly, the biggest visual archive humankind has ever known.

How big has that archive become? Well, Facebook already stores more than 140 billion of our photos. That’s one of those crazy number it’s impossible to make sense of, so here’s a bit of context:

Facebook’s image database compared to the biggest traditional archives

Getty Images, one of the world’s largest commercial photo libraries holds a total of 80 million images, the US Library of Congress holds about 15 million historical images, and the BBC photo archive around 10 million.

It’s less than six years since Facebook became a tool anyone could use, yet already it completely dwarfs all three. And although it’s by far the largest, it’s only one of many, many places we share pieces of our lives online.

So for the first time in history, ordinary people are recording the world around them on a massive scale.

Although photography became accessible to the masses about a hundred years ago, until very recently the costs were prohibitive enough that most of us only recorded life’s big events. Now we record everything: big events like never before, little events, and the apparently mundane.

The future historical value of that is obvious, but we’re in danger of missing this opportunity. Here’s why.

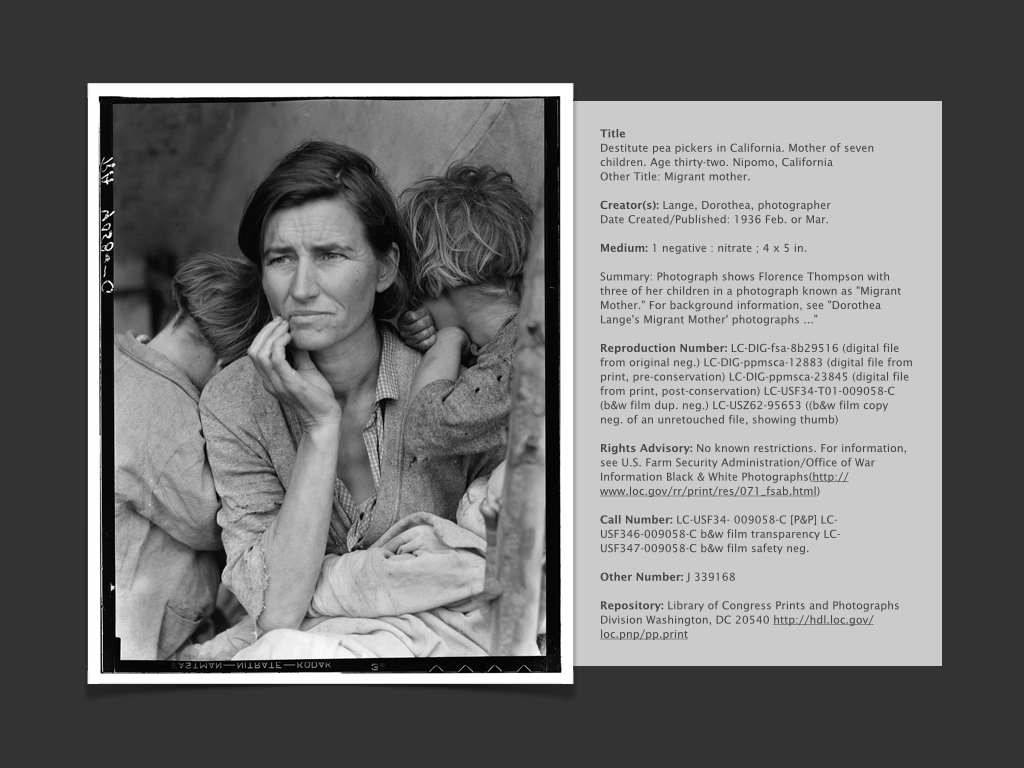

Every image in the Library of Congress archive is annotated with a pile of additional information, or metadata. Here’s one of its most famous images:

Migrant mother, Dorothea Lange

It comes with a detailed description of the photograph, the date taken, the location, the photographer, references to other pieces of content, and so on. The collection has been carefully curated and annotated, and it’s freely available to all. This is what gives it value as a historical reference.

By contrast, here’s a typical Facebook photo:

I discovered a study recently, which showed alcohol was a factor in 76% of the photos uploaded to Facebook by people in the UK.

I don’t think this means we’re a nation of drunkards, but I do think it’s further evidence that the content we populate social media with is all about the here and now. We actually expect most of it to be forgotten quickly – we’re not thinking about its lasting value. But unlike the shoebox of prints in our attic, it will be there for many, many years to come. This stuff will probably outlive everyone alive today.

So, while we’re building archives of content at rate never seen before, its value as a future historical record is way out of balance with its scale. This is because it’s not open, it’s badly indexed, and there’s quite simply too much of it.

Future generations are going to curse us, because we were the first with the chance to leave a detailed legacy of the things which were important to us. But we didn’t. We were so concerned about sharing in the present that we left them less useful information than our grandparents and their Box Brownies did.

In the same way new motorways fill with cars, and our waistlines expand the cheaper high-calorie food becomes, we seem to want to create and share as much content as current technology will allow. If we’re to seize the opportunity in front of us, we need some self-constraint. If we can’t find it, we’ll be leaving it up to the cultural elite to choose, again, which of this generation’s stories form part of our future history.

Seven and a half years ago, I decided to take a photograph every day, write down a thought or experience and share it openly online. Like every other hobby I took up, I thought I’d quickly get bored. But I discovered that as a day-to-day discipline it was a lot of fun, hugely addictive, and surprisingly captivating for others.

And after doing this for just a few months, I realised I was creating something of immense personal value. I was able to look back and remember, in an instant, what I’d been doing on a particular day. I still take over 10,000 photos a year, but my daily photo journal forces me to whittle that down to just 365 I want to share publicly – one representing each day of my life.

Since I took and shared that first picture seven years ago, my idea has blossomed, and I now find myself at the centre of a worldwide community of tens of thousands of ordinary people doing the same – taking and sharing just one picture a day. Every month we grow in numbers and although we all get a buzz out of it on an individual level, I’ve realised that collectively we’re creating history, one day at the time.

Blipfoto is still in its infancy, but we’re already getting a real sense of the potential value of what we’re doing.

When something big happens, like the Christchurch earthquake twelve months ago, we’re flooded with an incredibly detailed photographic record. But what brings these images to life are the stories which support them. Like this shot, which on first glance appears just to show a damaged building:

But the accompanying text tells us the blue shape in the foreground is in fact a dead body, covered but not yet removed.

Or this man, quietly peeling an apple for his wife, the photographer:

She tells us that he’s kept the light for years in case of an emergency like this, along with a bottle of kerosene to fuel it. She talks about her feelings, her relief that family and friends are safe and well, and that they have somewhere to sleep – the only things that seem important any more.

Or the teams working tirelessly to clean up the silt which has risen into their neighbours’ gardens from below, even though their houses have been condemned and are expected to be demolished:

And the guys helping to clear out people’s possessions before the roofs of their houses come tumbling in:

One of my favourite stories is from the person who arrived home to find their house still standing, but everything they owned covered in their home made plum sauce:

They couldn’t imagine wanting to taste the stuff ever again.

All these individual, small stories, combine to give a much bigger sense of an event like this and, perhaps more importantly, ordinary people’s reaction to it. In this case, that reaction seems overwhelmingly positive and optimistic – a sentiment mainstream media might not record. And of course these images are supported by the camera’s metadata – date, time and, increasingly, location.

Now I’d like you to meet Ron.

Ron’s a senior manager at a group of brick factories in the West Midlands here in the UK. He’s almost five years into his daily photo journal, simply keeping a record of what he does day to day. A lot of that’s about family life, but because his working life is in the brick making industry, that’s a significant part of what he documents.

For us enjoying his journal in the present day, it’s a fascinating insight into an old industry most are probably unaware still exists. He shares all sorts of geeky technical detail about the process, like this kiln, being fired up to over a thousand degrees centigrade:

Or the ‘specials’ man, who’s responsible for producing the custom-made, special order bricks:

But a sad story soon emerged from Ron’s journal, as he was tasked with closing down first one, then two, then all of his factories, putting himself and all those working under him out of a job.

He talks quite openly about the process, and his feelings about the demise of the British brick making industry.

Ron’s building a unique historical record about a subject nobody is better placed to document. But that’s not why he keeps his journal.

He keeps his journal because he enjoys photography, and wants to share his day to day experiences with the rest of the world. Just like those who upload their photos to Facebook, he’s inadvertently building an archive. But, because he accompanies his photos with words and only shares one a day, its value is massively increased.

Events don’t have to be big, and stories don’t have to be unique. The most ordinary, everyday events we all experience are a wonderful way of understanding the differences and similarities across time and space. The first day at school is a perfect example:

What are the children wearing? What do they and their parents have to say about this new chapter in their lives? What challenges do they face, unique to their generation? How do they feel about what the future brings?

What I’ve discovered through the Blipfoto experience is that a few simple constraints can have a huge impact on the way we behave.

We can force ourselves to self-curate, editing our mass of content down to the most pertinent bits. We can be encouraged to share things openly, and we can make annotating and indexing part of the fun.

It’s the combination of these three things which will give the throwaway moments of today much more significance in the future.

So we should be building more tools with these principles at their core. If we do, I think we’re in with a chance of creating the first truly collective human history – accurate, insightful, and freely available to the future.

And that’s my idea worth sharing.